|

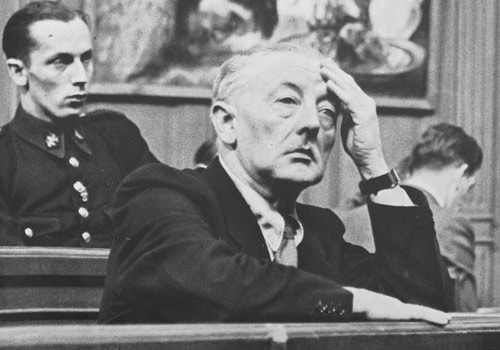

This article is about the fascinating topic of the art forger who fooled the connoisseurs of the art world and also the Nazi's second most powerful leader. The story of Han van Meergeren, the Dutch forger who successfully fooled the art world with his forgery of Johannes Vermeer's paintings, is a remarkable one that highlights the fine line between artistry and deception.

Who Was Han Van Meegeren?

Van Meergeren was an accomplished painter in his own right, but struggled to gain recognition for his work. In the 1930s, he began experimenting with creating forgery of Vermeer's master pieces, driven by a desire to prove the art critiques and experts wrong for dismissing his own paintings. His first major forgery was The Disciple at Emmaus, which he passed off as a long lost Vermeer painting in 1937. The forgery was so convincing that it was authenticated by leading experts and acquired by the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam for a then record price. The museum paid an astonishing 1.6 million guilders, equivalent to around $5.6 million today. This was a record price for a work attributed to Vermeer at the time. By today's standards, a Vermeer would command much higher prices, but that's inflation for you. Emboldened by his success, Van Meergeren went on to create several other Vermeer forgeries, including the Last Supper and the Christ and the Adulteress. His forgeries were so skillfully executed that they fooled even the most discerning experts, and his fame as a discoverer of lost Vermeer masterpieces grew.

How did He Do It?

Van Meergeren employed a fascinating array of ingenious techniques and materials to create his convincing Vermeer forgery. Here are some of the notable methods he used. One of the techniques he used involved the material called Bakelite. A Bakelite is an early plastic material invented in 1907, and he used Bakelite to harden and age the oil paints he used. He mixed Bakelite into his paints, causing them to dry and crack like centuries-old paintings. This cracking effect was crucial in making his forgery appear authentically aged. Van Meergeren would bake his finished paintings in an oven or subject them to extreme temperature fluctuations to induce cracks, brittleness, and other signs of aging in the canvas and paint layers. I experimented over and over and over again, showing an incredible persistence in his quest to master this forging technique. He also used phenol formaldehyde, a resin commonly used in the early 20th century to create a yellowed and aged appearance in the varnish layers of his forgery, mimicking the effects of centuries of oxidation. Van Meergeren sourced and used historical pigments like lead white, which was common in Vermeer's time, but had pretty much fallen out of use by the 20th century. This helped him to accurately reproduce Vermeer's distinct color palette. To further enhance the illusion of age, Van Meergeren would often paint over old canvases or use aged wooden stretches and panels that were contemporaneous with the 17th century. He studied and meticulously replicated Vermeer's renowned glazing techniques, applying thin transparent layers of paint to achieve the luminous and optical effects, characteristic of the Dutch master's work. Van Meergeren employed various methods to artificially age and distress his forgery's such as rubbing them with sandpaper or applying chemical solutions or even burying them in the ground for a period of time to develop a patina and simulate the effects of aging. Beyond the physical aspects of the forgery's Van Meergeren was also adept at creating convincing backstories and fabricating provenance documentation to support the supposed origins and histories of his newly discovered Vermeer paintings. These innovative uses of modern materials, combined with his meticulous study and use of historical techniques. Also, his willingness to go to great lengths to age and distress his forgeries made his deceptions incredibly convincing. This blend of artistry and deception was essential to pull off possibly the biggest art scandals of the 20th century.

Why Vermeer Paintings?

But why Vermeer? After all, one of the rules of art forgers is to pick a subject that is not in the spotlight. A famous artist that is not a super star in the art world. You may be able to slide your forgery through under the radar, so to speak. Today Vermeer is such a super star. But back in the 1930’s Vermeer’s works were not quite as famous as they are today. Imagine finding a long lost Vermeer? Now that was a tantalizing idea. The enigmatic nature of Johannes Vermeer's life and body of work contributed significantly to the success of Van Meergeren forgeries. The lack of concrete information about Vermeer created a fertile ground for deception and speculation, which Van Meergeren expertly exploited. Unlike his contemporaries like Rembrandt and Franz Hals, who left behind a wealth of biographical details, personal records, and a substantial number of works, Vermeer remains an elusive figure in the history of art. Apart from a few archival records and the handful of paintings attributed to him, there is very little factual information about his life, personality, or working methods, or even what he looked like. This scarcity of knowledge allowed Van Meergeren to operate within a vacuum, crafting a narrative in a style that could not be easily contradicted or disproven. The experts and collectors who authenticated his forgery had little concrete evidence to compare them, making it easier for Van Meergeren's works to slip through the cracks of scrutiny. The mystiques surrounding Vermeer's small body of work added to the allure of discovering new works by the master. The idea of unearthing a previously unknown Vermeer was tantalizing, and precisely because of the rarity and preciousness associated with his work. Van Meergeren capitalized on this desire for revelation, creating forgery that seemed to fit into the gaps and uncertain certainty surrounding Vermeer's autistic output. The lack of a comprehensive understanding of Vermeer's techniques, materials, and stylistic evolution made it easier for Van Meergeren to craft convincing imitations that could be interpreted as part of the master's undocumented period or creative process. Also, the scarcity of Vermeer's works also contributed to a sense of reverence and a heightened eagerness to accept any newly discovered paintings as genuine. The fear of missing out on an opportunity to acquire a rare Vermeer further clouded the judgment of collectors and experts. In essence, a lot of mystery surrounding Vermeer's life and work played right into Van Meergeren's hands, allowing him to exploit the gaps in knowledge. The deception took root because there was no definitive reference point against which to judge the authenticity of the forgery's. And the allure of uncovering a lost masterpiece was simply too strong to resist, especially for some experts with rather large egos. Now, the fact is, Van Meergeren's forgeries are actually very ugly paintings. If you look at the pictures of these forgery's and compare them to Vermeer's known work, you will not see any connection, and you'll wonder what these people were thinking. So this brings us onto this fascinating paradox in the art world, the interplay between artistic skill, deception, and the power of desire and belief. While Van Meergeren was undoubtedly a skilled painter, his work was objectively not on the same level as Vermeer's masterpieces. However, what made his forgery so successful was not necessarily their artistic merit, but rather the psychological allure of the idea of discovering an unknown work by a revered master like Vermeer.

The Paradox of Human Psychology

Collectors, art experts, and enthusiasts alike were so captivated by the prospect of unearthing a lost treasure that they allowed their desires and preconceptions to cloud their judgment. The notion of finding a new Vermeer was so tantalizing that they were willing to overlook or rationalize any potential flaws or inconsistencies in Van Meergeren's forgery. This paradox reveals the power of human psychology and the influence of subjective factors in the appreciation and validation of art. While the art world prides itself on objectivity and expertise, Van Meergeren's deception exposed vulnerability. The yearning for discovery and the desire to believe in the existence of a hidden masterpiece can override critical analysis and skepticism. The experts and collectors involved were not necessarily incompetent or lacking knowledge. Rather, they fell victim to their own aspirations and biases. The forgery fulfilled a deeply held wish to discover a new Vermeer, and Van Meergeren exploited the psychological factor. Apparently, after the forgery was revealed later on, these very same experts could not believe that they had fallen for his tricks. So I guess it's also a commentary on the human condition, our susceptibility to self-delusion, our tendency to see what we want to see, and the allure of the extraordinary, even in the face of reason and evidence. These forgery were not submitted to expert scrutiny and analysis, even though I suppose a lot of modern techniques were not available back then. What Happened to Van Meergeren? So what happened to Van Meergeren? Well, he made a lot of money. He lived a life of hedonistic pleasure. He wasn't married. He held lavish parties, and he certainly made the most of his windfalls. Even though the Netherlands were going through some tough times, even during the Second World War, Van Meergeren lived in a large house, didn't really seem to be selling any of his own art, and yet he was making all of this money. But nobody really seemed to put two and two together. It also needs to be remembered that Van Meergeren used intermediaries to sell his work. So It wasn't a case of the museum buying the paintings directly from Van Meergeren. They bought it from an agent who apparently got the painting from some other source, let's say a deceased estate or something like that. All of this provenance was, of course, crafted by Van Meergeren, and he set up his stooges and agents to approach museums and so on. So none of these museums or experts linked the paintings to van Meergeren in any form. So how did he get his comeuppance? Van Meegeren's undoing came during World War II when he sold one of his forgery, called Christ and the Adulteress, to the notorious Nazi leader, Herman Goring. Goring paid 1.65 million guilders, which is equivalent to around $7.3 million today. And this was an even higher price than that paid for the disciple at Emmaus. Goring was an avid art collector and was pillaging art throughout Europe. Oddly, though, he did pay for art in many cases where confiscation could not be justified, well, justified to the rapacious methods of the Nazis, of course. After the war, Dutch authorities investigated the sale, suspecting that Van Meergeren had sold a genuine Vermeer to the Nazis. And this, of course, was considered to be selling a national treasure to the enemy. The Investigation Begins In fact, it was only three weeks after the war ended that the investigator knocked on Van Meergeren's door to follow up on this sale. So facing prosecution for selling a Dutch cultural heritage, Van Meergeren had no choice but to reveal his secret. The painting he had sold to Goring was not a genuine Vermeer, but rather one of his own forgery. To prove his claim, he painted another forgery in the presence of experts and journalists in the courtroom, and he replicated his techniques sufficiently to convince the court that he did indeed forge the painting sold to Goring. But Van Meergeren's trial in 1947 became a media sensation, with the forger presenting himself as a patriot who had outwitted the Nazis by selling them a worthless forgery.

Hero or Common Criminal?

Despite the charges of forgery, and fraud, many Dutch citizens saw him as a hero who had duped the enemy and protected a national treasure. In the end, von Mirgeren was convicted but received a relatively light sentence of one year in prison. Sadly, though, Van Meergeren died shortly after being sentenced, and he did not, in fact, serve any time. He died of a heart attack, and he wasn't that old either in his late 50s, but he certainly had gone through quite a lot of stress, one can imagine. But you may be wondering how the Dutch authorities managed to link up the sale to Van Meergeren in the first place, since he used intermediaries. Initially after World War II, the Dutch authorities were investigating the sale of the purported Vermeer painting to Goring. The trail led investigators to a Dutch art dealer called Abraham Bredius, who had acted as an intermediary in the sale. However, Bredius had passed away, and the authorities struggled to find concrete evidence tying the sale directly to the forger. The breakthrough came when one of Van Meergeren's former associates, who was facing financial troubles, revealed to the authorities that Van Meergeren had confessed to him about forging the Vermeer sold to Goring. So armed with this lead, the police raided Van Meergeren's home and studio in Amsterdam, where they found numerous materials and tools used in the forgery process, including bakelite, lead primer, and aged canvases. Additionally, they discovered a previously unknown Vermeer forgery that was still in progress, which Van Meergeren had not yet completed. With this physical evidence and the testimony from his former associate, the authorities were able to make a direct connection between Van Meergeren and the sale of the forged Christ and the Adulteress to Goring. Greed and Ambition: The Price of Art Let's have a look at the issue of high prices. Why such high prices and why a lack of caution when buying paintings like this. It sheds light not only on the psychological and market forces that drive the exorbitant prices paid for masterworks, but also whether artistic merit Is that significant? Also, the lack of research by a lot of collectors. It's almost as if collectors simply want the painting to be genuine rather than testing whether it is, in fact, a genuine painting. At its core, the allure of earning a rare and prestigious masterpiece is often more about the psychological factors than the objective artistic accomplishment of the work itself. Just as collectors were seduced by the idea of discovering a new Vermeer, the ultra wealthy today are drawn to the prestige, scarcity, and cultural cachet associated with owning a work by a renowned master. Owning a masterpiece becomes a status symbol, a way to signal one's wealth, taste, and cultural sophistication. The astronomical prices paid at high-profile auctions today are not necessarily reflective of the work's autistic value, but rather a manifestation of the desire to possess something rare, exclusive, and historically significant. There's also an interplay of psychology, brilliant salesmanship by galleries and auction houses, and the perception of art as a tangible investment asset. As long as prices go up, the investment aspect is justified. Galleries and auction houses are adept at creating narratives and cultivating an aura of exclusivity around certain works, playing on the collector's desire for rarity and bragging rights. Also, the art world's opaque pricing mechanisms and the subjective nature of art valuation also contribute to the escalation of prices. Scarcity, provenance, and the artist's reputation become more important than the inherent artistic merit, allowing for works of questionable quality to command staggering sons. Van Meergeren's paintings are a good example of that as well. But maybe you've seen modern art that you really cannot quite understand what all the fuss is about. While some collectors genuinely appreciate the artistic quality of the work they acquire, for many, the allure of owning a masterpiece and the desire for social status and the potential for investment returns overwrite any objective considerations. The Modern World of Forgeries So are there still modern forgery in the 21st century? Have collectors and auction houses all cottoned on to all the schemes? Or is forgery still a big factor? Well, the short answer is yes. Particularly modern art abstract abstract art, works like that are somewhat easier to forge. And it's estimated that up to 40% of the art sold in the world as collectible art is in fact forgery. There are a few examples of famous cases in the 21st century. The Wolfgang Beltracchi case. German artist Wolfgang Beltracki and His accomplices were responsible for one of the most prolific art forgery rings in recent history. Between the 1990s and 2010, Beltracchi forged and sold hundreds of paintings, including works attributed to famous artists like Max Ernst, Fernand Leger, and Max Peckstein. His forgery fetched over $45 million on the art market before his arrest in 2010, and the scandal shook the art establishment and raised serious questions about authentication processes. Then there was the case of the Knoedler Gallery. I hope I've pronounced that right. The Knoedler Gallery is one of the most respected art galleries in New York. It was embroiled in a forgery scandal that unraveled in the early 2000s. The gallery had sold over $60 million worth of fake abstract expressionist paintings purportedly by artists like Jackson Pollock, Martha Rothko, and Robert Motherwell. The forgery was created by an unknown artist and was accompanied by elaborate back stories and provenance. Always very important. The scandal led to numerous lawsuits and has tarnished the gallery's reputation. Then there was the case of the fake Chinese masterpieces in The 2010s, a series of forgery of ancient Chinese masterpieces flooded the art market, particularly in the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong. Several renowned auction houses, including Sothebys and Christie's, were caught up in the scandal, having auctioned and authenticated these fake works for millions of dollars. The scandal exposed vulnerabilities in the authentication processes for Chinese antiquities and has apparently led to increased scrutiny of these artworks. Then there is another one called the Art Con case. In 2018, a group of individuals, including a painter and an art dealer were charged in an art forgery scheme that they had been operating for over 15 years. They had created and sold fake works attributed to artists like Willem de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Stuart Davis, earning millions of dollars. So significant financial losses for collectors, galleries, and auction houses, and also undermining the trust in the art markets authentication process. I wonder if the commissions have anything to do with overlooking some of those processes. It's a high-risk game sometimes. So what happened to Van Meergeren's forgery? Were they destroyed? The answer is no. The forgery created by Han van Meergeren that were purchased by museums were not destroyed after his deception was revealed. Instead, many of these forge paintings have been retained by the institutions that acquired them, serving as educational examples and reminders of one of the most notorious art frauds in history. Somewhat to the chagrin of some of these museums, a lot of tourists and art connoisseurs can't help but ask to see Van Meergeren's paintings, and these are currently kept in storage. So if you can get a viewing of one of his paintings, it might be confusing. What happened to some of his specific paintings? The Disciple at Emmaus from 1937. This was Van Meergeren's first major forgery, and it was purchased by the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam. So after this forgery was exposed, the museum kept the painting as an important example of Van Meergeren's deceptions. The Emmaus Painting that was purchased by the Rotterdam Amsterdam gallery owner, Abraham Frost. After Van Meergeren's trial, the painting was returned to Frost's widow, and it eventually ended up in possession of the Boijmans Museum. Christ and the Adulteress, the famous painting sold to Hermann Goring. After the war, it was confiscated by the Allied forces and later returned to the Dutch government. It is also now part of the collection at the Boijmans Museum. Apparently, Goring was terrifically upset when it was revealed to him that the painting was in fact a forgery. Of course, he was in jail and going through the Nuremberg trials, but he seemed more upset about his fake Vermeer. The Disciple at Emmaus, that painting was acquired by the Rembrandt Association in Amsterdam and has remained in their collection. So rather than destroying the forgery, museums and institutions recognize their value as educational tools. And a good example and a warning to anyone purchasing such masterpieces, alleged masterpieces, to do some homework. They serve as cautionary tales for the art world and highlight the importance of rigorous authentication processes. Additionally, art historians can study the forger's techniques, materials, and methods, and give them things to look out for in the future. So what do you think of Han Van Meergeren's audacity and His interesting comeuppance at the end of World War II? Certainly a fascinating story, and also one that points to, well, our fascination with masterpieces. But also, if you had the money, would you buy a painting like that? If it was revealed to you, what steps would you take to check it out? And Well, for most of us, this is not going to be something that we're going to encounter. But who knows? You may uncover something in an art shop or an attic or something like that. It could be a lost Masterpiece or a forgery tucked away. I certainly found this story very interesting, although forgery is not a topic that I particularly look out for. I do find it fascinating, though, seeing how these capers work out. We always think that the people who buy these paintings must have been really foolish, but are we so different? Can we also get misled and excited about something that seems so fantastic and such a fantastic opportunity, and it all turns out to be a fake. As they say, buy paintings from living artists. At least you'll be able to check on the provenance a lot easier. Well, if you enjoyed this podcast, let me know in the comments. Give the podcast a review if you can, and a thumbs up. Share it with your friends. It'd be great to get the story around and provide something a little bit different in the world of art history as well. If you want to find out more about painting in general, check out my art school. And maybe I will meet you in one of my art courses or in my monthly live channel. Each month I do a live class and my students get to download the references and try the paintings for themselves. It's a lot of fun and it will certainly help your painting to improve very quickly. Look out for the Artists Live channel. |

AuthorMalcolm Dewey: Artist. Country: South Africa Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

FREE

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed